by

Robert Todd Mitchell

Liberty University

A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Education

Liberty University

2018

APPROVED BY:

James Swezey, Ed.D., Committee Chair

Deanna Keith, Ed.D., Committee Member

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this phenomenological study is to describe the lived experiences of students who graduated from modern classical Christian schools. The theoretical framework utilized is Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (SLT) as it relates to his concept of academic self-efficacy (ASE). Bandura (1986) posited that there are four constructs that serve as predictors in the development of ASE: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and physiological response. To address the research problem, I identified a purposive criteria sampling of 8 participants who graduated from accredited and member ACCS schools having experienced all three components of the trivium. Of the eight participants, five maintained a journal entering qualitative responses that described their respective ACCS school experience. All eight participants were interviewed using semi-structured, open-ended questions that allowed for follow-up discussion and elaboration. Finally, I facilitated a focus group interview with four of the eight participants, which was guided by semi-structured questions designed to elicit discussion on the emerging themes from the interviews and journals. The data was analyzed using Moustakas’ (1994) seven step model of transcendental phenomenology. The research resulted in a Kingdom-oriented, composite, metaphorical description of student experiences in trivium-based education within ACCS schools.

Keywords: classical Christian education, grammar, liberal arts, logic, paideia, quadrivium, rhetoric, trivium.

Dedication

The Psalmist says, “Behold, children are a heritage from the LORD, the fruit of the womb a reward” (127:3, English Standard Version). I dedicate this work to my bride, Tricia, and our heritage: Hallie Kathryn, Jacob, Caleb, Caroline, Olivia, and Virginia Leigh. May you all never cease to learn and inquire about the depths of God’s wonder.

Acknowledgments

I must acknowledge that this work will not be completed without the dedicated encouragement from my wife, Tricia. I was originally compelled to pursue the doctoral level degree by my father, Richard Dale Mitchell, who modeled a work ethic second to none and always assured me of his pride and love for me.

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT

Dedication

Acknowledgments

List of Tables

List of Abbreviations

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Overview

Background

Historical Context

Social Context

Theoretical Context

Situation to Self

Problem Statement

Purpose Statement

Significance of the Study

Research Questions

Central Question

Subordinate Questions

Definitions

Summary

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

Overview

Theoretical Framework

Self-Efficacy

Academic Self-Efficacy

Related Literature

Christian Education

Trivium-Based Education

Historical Foundations of the Trivium

Classical and Christian Education

Contemporary Theorists of Classical Education

Contemporary CCE Research

Student Descriptions of Educational Environments

A Framework for Lived Experiences

Summary

CHAPTER THREE: METHODS

Overview

Design

Research Questions

Setting

Participants

Procedures

The Researcher’s Role

Data Collection

Interviews

Journaling

Focus Group

Data Analysis

Bracketing

Horizontalizing

Clustering Horizons

Coherent Textural Descriptions

Imaginative Variation

Trustworthiness

Credibility

Dependability and Confirmability

Transferability

Ethical Considerations

Summary

CHAPTER FOUR: FINDINGS

Overview

Participants

Sophia – Veritas Classical Christian School (VCCS)

Lyla – Paideia Classical School (PCS)

Libby – Veritas Classical Christian School

Mya – Paideia Classical Christian Academy (PCCA)

Marleigh – Cornerstone Classical Academy (CCA)

Oak – Paideia Classical Christian Academy

Kain – Trinity Classical Academy (TCA)

Mason – Covenant Christian School (CCS)

Development of the Composite Description

Narrative Responses to Research Questions

Summary

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSIONS

Overview

Summary of Findings

Discussion

Theoretical Framework

Related Literature

Implications

Theoretical Implications

Empirical Implications

Practical Implications

Delimitations and Limitations

Recommendations for Future Research

Summary

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

Appendix A: IRB Approval Letter

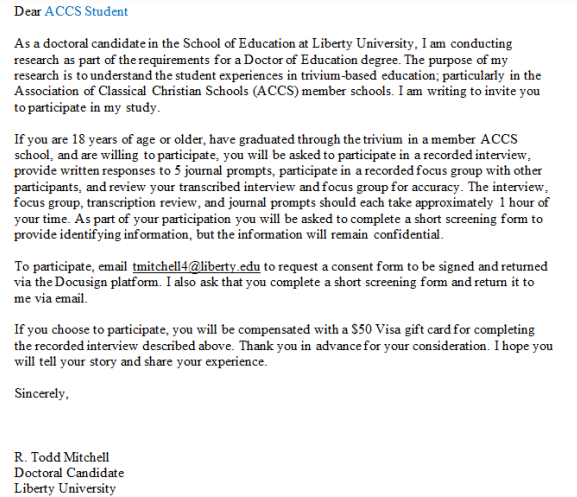

Appendix B: Recruitment Letter

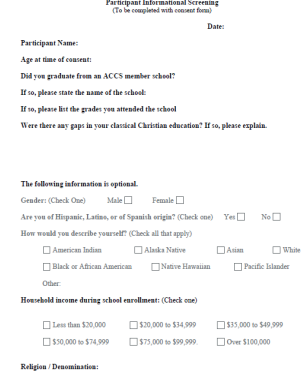

Appendix C: Demographic Screener

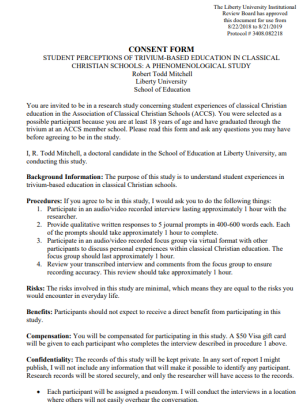

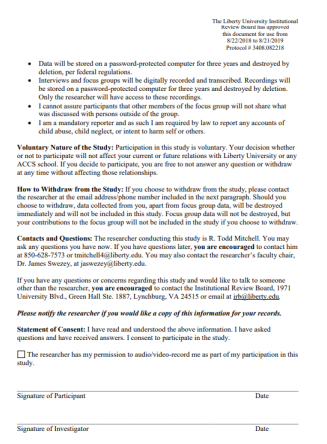

Appendix D: Consent Form

Appendix E: Thank You Letter to Co-Researchers

Appendix F: Interview Questions

List of Tables

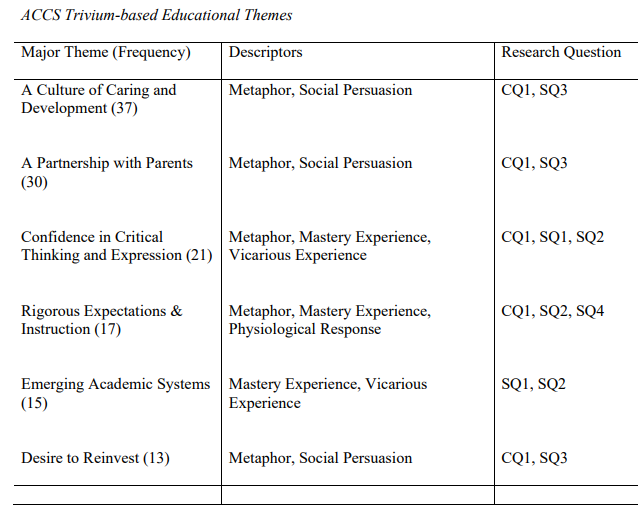

Table 1

List of Abbreviations

Association of Classical Christian Schools (ACCS)

Cornerstone Classical Academy (CCA)

Classical Christian Education (CCE)

Covenant Christian School (CCS)

English Standard Version (ESV)

Individual Education Plan (IEP)

Paideia Classical Christian Academy (PCCA)

Paideia Classical School (PCS)

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)

Social Learning Theory (SLT)

Trinity Classical Academy (TCA)

Veritas Classical Christian School (VCCS)

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Overview

Since the early 1990s Christian education has undergone an expansion of sorts with the emergence of a classical educational paradigm. The Association of Classical Christian Schools (ACCS) began as an accrediting organization in 1993 with 10 member schools in the United States. As of the 2015-16 school year, the same organization had grown to 247 members worldwide; an equivalent growth rate of 96% in 22 years (ACCS, 2016). In the modern sense, classical Christian education (CCE) mimics the enlightenment training given to students in ancient civilizations like that of Greece and Rome, combined with an even greater emphasis on a Christian worldview. While evidence exists to show significant growth among ACCS schools, this study will seek to describe the students’ perception of the pedagogy in this modern sense. Chapter One surveys the historical, social, and theoretical context of the study to be performed. Moreover, the chapter includes a discussion on why I, the researcher, am motivated to perform this particular study and the philosophical assumptions, worldview, and paradigm that I bring to the research. Chapter One concludes with a discussion of the problem to be addressed throughout the research, the purpose and significance of the study, and the research questions that will guide the inquiry.

Background

The preponderance of literature written on the topic of classical education are ancient philosophical writings that discuss the efficacy and implementation of the pedagogy in specific cultural settings. While classical pedagogy has made a resurgence of late in America, the pedagogy has deep roots in ancient civilizations (Scott, 1999). The trivium—a language arts curriculum developed by the Greeks and later codified in late antiquity by the Roman, Martianus Capella, is considered to be the entrance to and core of the classical pedagogy (Scott, 1999). The ACCS and CCE were born out of this rich tradition and a deep understanding of their historical, social, and theoretical context is important.

Historical Context

Veith (2012) stated, “Classical education is a method of education rooted in the classic, especially Ancient Greek and Latin, based on the seven liberal arts comprised of the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the quadrivium (astronomy, arithmetic, music, and geometry)” (p. 2). The medieval components of the trivium and quadrivium comprise what classical educators refer to as the seven liberal arts. The trivium, the first three components of liberal arts education, are the preliminary courses where primary, intermediate, and secondary students learn how to think about truth and reality. In her speech delivered to Oxford University, Sayers (1948) had this to say about the trivium:

Now the first thing we notice is that these “subjects” are not what we should call “subjects” at all: they are only methods of dealing with subjects. Grammar, indeed, is a “subject” in the sense that it does mean definitely learning a language‐‐at that period it meant learning Latin. But language itself is simply the medium in which thought is expressed. The whole of the Trivium was, in fact, intended to teach the pupil the proper use of the tools of learning, before he began to apply them to “subjects” at all. First, he learned a language; not just how to order a meal in a foreign language, but the structure of a language, and hence of language itself‐‐what it was, how it was put together, and how it worked. Secondly, he learned how to use language; how to define his terms and make accurate statements; how to construct an argument and how to detect fallacies in argument. Dialectic, that is to say, embraced Logic and Disputation. Thirdly, he learned to express himself in language‐‐how to say what he had to say elegantly and persuasively. (p. 4)

In grammar, students learn the basic building blocks of reality, be they words, numbers, or a simple concept in any subject area. For instance, the grammar of mathematics would be the concepts of numbers, addition, or a number line. In logic, students learn to think about how those basic building blocks fit together in an orderly fashion. In rhetoric, students learn how to communicate winsomely about those various building blocks and to communicate with wisdom as to how those parts interact with one another. The quadrivium, the last four components of liberal arts education, are the secondary subjects where students develop expertise in a particular field of study (Sayers, 1948). These four subjects were historically studied following the mastery of the trivium. In a modern sense, they would compare with university studies at the collegiate level.

Boutin and Rogers (2011) argued that upon examination of educational means from the classical period into the Roman Empire, one could find a common goal of producing useful citizens. It was this common goal of useful citizenship that, in addition to political ideology, also had influenced the United States in its infancy. “The beginnings of Western educational thought are as evident in Greece and Rome as are origins of Western political structures” (Boutin & Rogers, 2011, p. 400). The purpose of Boutin and Rodgers’ research was to examine the classical roots of Thomas Jefferson’s personal education and the influence that those classical roots had on what he believed to be his ideal curriculum for students in that age. That ideal curriculum entailed the use of the trivium similar to its use in ancient Greece and Rome.

However, the use of the trivium fell out of favor with modern American educators as Dewey’s (1922) pragmatism influenced the educational landscape during the world war eras. These educators generally thought the modes of the trivium were incompatible with the modes of learning in the contemporary student. While literacy remained the primary focus of educators during this time, the trivium was superseded by other educational paradigms thought to be more valuable. Abeles (2014) asserted that post-secondary education had undergone substantive change since the development of the trivium and the quadrivium as the core curriculum; particularly toward the end of the eighteenth century.

To the contrary, beginning around the early 1980s, some educators began to realize the well-suited design that the trivium provided today’s students. Douglas Wilson, a pastor in Moscow, Idaho and founder of The Logos School, published Rediscovering the Lost Tools of Learning. In it Wilson (1991) recounted an essay written by Dorothy Sayers. Sayers (1948), a classicist, author, and Christian wrote The Lost Tools of Learning, pointing out the dangerous shift away from classical education during the time of Dewey (1922). Wilson concurred with Sayer’s essay when she described the ancient foundation of education, the trivium, and explained why it was still essential even in its modern sense. From these writings, and the pioneering of several Christian educators and American families, was born the modern movement of the ACCS.

Social Context

This research will study the participant perceptions who attended ACCS schools for the entirety of their primary, intermediate, and secondary educational careers. For the purpose of this study, the social context of a generic private school environment was viewed as the setting to be studied. According to Bitterman, Gray, Goldring (2013) and the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) only 4% of private school students in America received Title I services as compared to 37% in traditional public schools and 49% in public charter schools. This speaks to the typical income of the households who attend private school. Families earning above a specific level of income are not eligible for Title I services (Bitterman et al., 2013). Private educational settings are comprised of families who are highly educated or individuals who place a great emphasis on education in general (Egalite & Wolf, 2016). Bitterman et al. (2013) found the average percentage of private school graduates who attended a 4-year college was 64% as compared to 40% for traditional public schools. Bitterman et al. (2013) also stated that approximately 98% of public schools had at least one student with an Individual Education Plan (IEP) for of special academic needs, while only 64% of private schools had at least one student with a formal IEP.

Beyond private school graduates, CCE graduates attend educational environments steeped in a Christian worldview where pedagogical practices are common to the ancient trivium. The social context of CCE students is aptly described in the following excerpt from the ACCS’ statement of faith.

The authority granted to fathers and mothers in Scripture is passed to the school in loco parentis. This means that, for the development of paideia in students while at school, the school operates with the same authority that fathers have in the raising of children. (ACCS, 2016, p.1)

Furthermore, the ACCS (2016) described their mission as treating theology as the queen of knowledge. Students are taught the medieval principle that every experience, every skill, every idea, all knowledge, and every creation is only understood in the context of God and His nature (ACCS, 2016). Classical Christian educators view education as the cultivation of virtue. Their mission is to teach children to think well (Intellectual Virtues), train them to lead (Cardinal virtues), transform them with a love of goodness (Moral Virtues), train them to be winsome as they write and speak with eloquence (Rhetorical virtues), deepen their knowledge of God, history, and our world (the virtue of Wisdom), and to immerse them in a Christian view of all things (ACCS, 2016).

Finally, CCE students function within the bounds of the trivium and are required to learn how to acquire knowledge using all five senses (Wright, 2015). Learning in CCE settings requires strong skills in memorization. Students discover and discern patterns in academic subjects, be they visual, casual, or structural. Practice and repetition are common tools used to guide in the finding of associations or relationships. Trivium schools place a high value on the importance of order, belief in objective truth, invention, commitment to universal truth, experimentation, evidence, and discipline (Wright, 2015). Furthermore, CCE students learn to appreciate and reflect on truth, goodness and beauty as they are cultivated as worshippers of the God of the Old and New Testament scriptures (ACCS, 2016).

Theoretical Context

CCE, in the modern sense, is to yet to undergo extensive empirical scrutiny, especially with regard to a specific theoretical lens. This study utilizes a specific component of Bandura’s (1971) SLT known as ASE. Guided by Bandura’s (1986) four predictors of self-efficacy (mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and philosophical response) this research categorizes and describes the lived experience of students within the phenomenon of CCE. The four predictors will serve as a framework for the descriptions provided by each participant.

ASE was chosen because the four predictors can be used to study the description of student experiences while simultaneously categorizing and evaluating the experiences as they relate to the effectiveness of the pedagogy. Each experience of the student, in the academic setting, can be classified into one of these four descriptors. Where the experience is classified, should determine the impact the experience had on the student’s ASE and how the student perceives their learning environment. An in-depth discussion of each level can be found in the Framework for Lived Experience section of Chapter Two.

Situation to Self

This research is born out of a desire to give voice to students who have experienced the phenomenon that is CCE. From a parental perspective, I echo the motto of the ACCS that says, “You’ll wish you could go back to school.” Having seen the opportunities afforded to students within the phenomenon, I understand that CCE uniquely positions students to excel academically, professionally, and spiritually. I did not experience the pedagogy firsthand as a student. However, my experience with CCE began as a homeschool parent-teacher and later included a position as a private school teacher and administrator. I have witnessed the remunerations of this pedagogy in my own children’s success and the students I have personally taught and served with as an administrator. However, in neither case did I experience the fulleffect, kindergarten through twelfth grade or grammar through rhetoric, of the phenomenon. I want to discover if student perceptions will align with the common perceptions of parents, ACCS patriarchs, or fellow teachers and administrators within classical Christian school sites.

According to Creswell (2018), qualitative research is born out of the worldview of the inquirer, observed through a particular theoretical lens, guided by specific research questions, and grounded in fixed philosophical assumptions. As I seek to understand the phenomenon, it is important that I identify my worldview, theoretical framework, guiding questions, and the assumptions that I intend to maintain throughout the study. The assumptions I will maintain throughout the study are ontological and axiological.

The ontological assumption of the study is that each student participant will show evidence of multiple realities, viewing their experience within the phenomenon as different. Moustakas (1994) asserted that phenomenological researchers are reporting how individuals participating in a study view their experiences through these various realities. The emphasis of this study will be to identify the common themes among the participants but only as they describe them singularly.

A second consideration must be given to my axiological assumptions as the researcher. It is important that I identify and disclose my personal values and how those values affect the proposed research. Creswell (2018) stated, “Inquirers admit the value-laden nature of the study and actively report their values and biases as well as the value-laden nature of information gathered from the field” (p. 21). I previously served as an ordained minister after earning a Master of Divinity degree. I approached this research with a Christian worldview. A critical component of the phenomenon under inquiry is the Christian worldview and Christian thought common among those schools employing the classical Christian pedagogy. Biblical integration is not just an appendage, but rather a primary emphasis of the curriculum. The combination of my personal experience and the norms of the ACCS schools have the potential to impact the interpretive process during the analysis phase of research.

Finally, after disclosing my biography and philosophical assumptions as they relate to the research, it is also important to discuss the interpretive paradigm to be used. As a social constructivist, I believe that learning is a constructive process. Therefore, my interpretation of the learning process is that learners are actively constructing their own subjective representations of reality. The learning process, while social, should then have a significant role in the lived experience of students and their descriptions. My Christian, constructivist worldview, along with the chosen theoretical framework, will be employed during this research to interpret the descriptions of students in their trivium-based educational environments.

Problem Statement

There is currently an absence of empirical research that describes the lived experience of students who were educated in a classical Christian school environment. In addition, the field of literature is sparse concerning student perceptions in general. Littlejohn and Evans (2006) explained that 75% of today’s needed workforce should be characterized as “knowledge workers,” (p. 11) while intellectual capital is at an all-time high. Littlejohn and Evans (2006) went on to state, “Demand for mere training in a particular trade or craft has faded with the industrial age, rendering the educational paradigms that catered to such demands obsolete. Instead, the need for men and women who can think outside the box pervades the American business culture” (p. 11). British scholar and noted Christian philosopher, Harry Blamires (1963) wrote about the absence of a shared field of discourse and Christian thinking on secular ideas in his work entitled The Christian Mind. In it, Blamires (1963) stated,

There is no Christian mind…Under all the frustrations of inactivity from which Churchmen suffer, under all the misuse of energy, mental and manual, which the Church delights in, and under the appalling catastrophe of a world cut off from the Church, there lies a deficiency, a gaping hole, where there ought to be the very bedrock basis of fruitful action, the Christian mind. (p. 43)

Blamires (1963) is emphasizing his belief that there is no conversation being had in which writers are reflecting christianly on the modern world and modern man. Classical educators believe that graduates of classical Christian schools are the incoming critical, Christian thinkers of the modern age and they are being enculturated into the paideia of God through education (ACCS, 2016; Wilson, 1999; & Wright, 2015). The problem to be examined by this study is whether students describe their experience in trivium-based education as an effective model for primary, intermediate, and secondary education and do they describe being able to think critically and christianly about the modern secular world. This empirical research intends to give voice to the students in this setting to determine if they describe the same outcomes as do the classical educators who train them.

The phenomenal growth of the ACCS demonstrates a tremendous buy-in from a critical mass of parents and families who are either convinced of the pedagogies benefits or influenced by the failures of the available alternatives (ACCS, 2016). In either case, the relevant statistics and lack of existing research uncover a need for understanding the essence of CCE, particularly from the student’s perspective. While literature exists that describe teacher and administrative perspectives, and anecdotal evidence exists to describe parental perspectives, students are yet to have a voice that describes their experience within the phenomenon.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this transcendental phenomenological study is to describe the lived experiences of students who graduated through trivium education and classical Christian schools at the primary, intermediate, and secondary level. For the purpose of this study, trivium-based education will be generally defined as the modern use of classical educational methods established by the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Middle Ages (Sayers, 1948). CCE will be generally defined as the integration of trivium-based education with a Christian worldview (Dernlan, 2013). The theoretical framework that will serve to advance this study will be Bandura’s (1971) Social Learning Theory (SLT) as it relates to ASE (Bandura, 1986). According to the theory, four constructs are instrumental in the development of an individual’s ASE: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and physiological response. These four constructs should significantly impact the student’s description of their lived experiences within the phenomenon of the trivium and classical Christian schools.

Significance of the Study

This research will provide benefits to a variety of stakeholders. The significance of this study will be described from an empirical, theoretical, and practical perspective. The empirical elements of the study will address the gaps in the literature regarding student perceptions of CCE. The theoretical elements will integrate the trivium with ASE as well as use its four predictors as a framework to describe student experience. Finally, the applied or practical significance of the study will address the effectiveness of the trivium’s use within Christian education.

The empirical significance of the study is that the research will add to the existing literature regarding student perceptions of educational experiences, particularly in CCE. This addition will serve to inform educational researchers who study pedagogy and curriculum. Furthermore, this supplementation to the literature will allow professional educators and administrators to gain helpful insight on student perspectives and allow CCE teachers to improve their own craft in the classroom (ACCS, 2016).

The theoretical significance of the research is that it will uniquely utilize the theoretical framework in conjunction with a trivium-based education, informing theorist of its usefulness or application. This research will demonstrate whether the constructs of SLT and ASE has the impact theorized by Bandura (1971) in terms of descriptions or narrative accounts. By serving as a framework for lived experiences in this research, future educational researchers should be able to use the four predictors in their narrative descriptions of student experiences in traditional,

unique, or novel educational environments.

Perhaps most important significance of this research are its practical applications. The applied significance of the study will be to determine if student perceptions align with the perceptions of teachers, parents, or the general public regarding the efficacy of the pedagogy (Veith & Kern, 2001). This practical application will inform parental stakeholders, CCE teachers, CCE administrators, and potential donors who desire to invest in the successful educational practices of ACCS schools. Additionally, the ACCS as an accrediting organization may gain practical insight into how they maintain or adopt new policies and procedures for accreditation, recruiting, and professional development.

Research Questions

The research questions are derived from the problem and purpose of the study. The questions are rooted in the literature available and not based on the agendas, personal passions, or curiosity of myself or any other stakeholder related to CCE. As was previously stated, the problem to be examined by this study is that students do not currently have a voice in the description of CCE or its effectiveness within the ACCS. The purpose of the study is to describe the lived experiences of students who graduated from these classical Christian schools.

Central Question

Scholars have argued that a return to classical education in American schools, while rejecting elitist traditions, could be accomplished through a well-designed program and would be academically beneficial for all stakeholders involved (Adler, 1983; Bauer, 2003; Sayers, 1948; Stanek, 2013; & Wilson, 1999). Moreover, because classical educators describe a rich cultural impact and ascribe such leadership potential from graduates of ACCS schools, student perceptions of pedagogy are relevant to the field of education and worthy of study (Wilson, 1999; Wright, 2015; & ACCS, 2016). This is certainly true since no empirical research exists giving students a voice regarding CCE (Jain, 2015; Stanek, 2013). Therefore, the central research question of this study is: How do graduates of classical Christian schools metaphorically describe their lived experiences during their trivium-based education?

Subordinate Questions

The goal of phenomenology is to study how individuals make meaning of their lived experience (Moustakas, 1994). The subordinate questions of the research are rooted in the developing framework for lived experiences of the participants and Bandura’s (1986) theoretical framework guiding the study. Bandura’s (1993) research findings related to ASE support the implementation of the four descriptors to be used as a framework to describe lived experiences. Additionally, Sayers (1948) research supports the concept of specific levels of learning that correspond to the three trivium stages. Therefore, the subordinate questions which will be used to determine student experiences are:

SQ1. How do participants describe their mastery experiences during the grammar, logic, or rhetoric levels of CCE (Bandura, 1993; Sayers, 1948)?

SQ2. How do participants describe their vicarious experiences during the grammar, logic, or rhetoric levels of CCE (Bandura, 1993; Sayers, 1948)?

SQ3. How do participants describe their socially persuasive experiences during the grammar, logic, or rhetoric levels of CCE (Bandura, 1993; Sayers, 1948)?

SQ4. How do participants describe their physiological response to adversity during the grammar, logic, or rhetoric levels of CCE (Bandura, 1993; Sayers, 1948)?

This research will use student descriptions that are categorized into metaphorical, mastery, vicarious, social, and physiological experiences as predictors of Bandura’s (1986) ASE and will be used to describe or make meaning of the lived experience. The answers to the central and subordinate research questions should provide a student evaluation to the overall educational quality provided by accredited ACCS (2016) schools.

Definitions

1. Trivium-based Education – The modern use of classical educational methods established by the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Middle Ages (Sayers, 1948).

2. Classical Christian Education – The integration of trivium-based education with a Christian worldview (Dernlan, 2013).

3. Paideia – Paideia is a word, derived from the Greek, which emphasized education being central to the classical mind. Going far beyond the scope and sequence of formal education, the paideia was all-encompassing and involved nothing less than the enculturation of the future citizen (Wilson, 1999).

4. Trivium – The qualitative arts, coined during the middle ages, it refers to “the three ways” and is the first three stages of the seven liberal arts in classical education; grammar, logic, rhetoric (Perrin, 2004).

5. Quadrivium – The quantitative arts, coined during the Middle Ages, it refers to “the four ways” and is the last four stages of the seven liberal arts in classical education; arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy (Perrin, 2004).

6. Grammar – (Content) Not just a subject, but rather the primitive years of schooling (primary and intermediate elementary) where the building blocks of knowledge are delivered. During the grammar stage of learning, the rules of phonics and spelling, rules of grammar (as a subject), poems, the vocabulary of foreign languages, the stories of history and literature, descriptions of plants and animals and the human body, the facts of mathematics, etc.…these make up the “grammar,” or the first stage of learning (Wise & Bauer, 1999).

7. Logic – (Thinking) The second phase of the classical education, the Logic stage occurs in middle school and is a time when the student begins to pay attention to cause and effect, to the relationships between different fields of knowledge, to the way facts fit together into a logical framework, or the way the parts or building blocks are ordered. It is here where the student’s capacity for abstract thought begins to mature (Wise & Bauer, 1999).

8. Rhetoric – (Expression) Rhetoric stage of learning occurs during the high school years, after the student learns to write and speak with force and originality. Building on the first two stages of learning, the student of rhetoric applies the rules of logic learned in middle school to the grammar or foundational information learned during the grammar stage. He expresses his conclusions in clear, forceful, winsome language. It is here where students begin to specialize in whatever branch of knowledge attracts them (Wise & Bauer, 1999).

9. Self-efficacy – A person’s beliefs about his or her own ability to produce certain desired results (Bandura, 1994).

10. Mastery experiences – “The most effective way of creating a strong sense of efficacy is through mastery experiences. Successes build a robust belief in one’s personal efficacy. Failures undermine it, especially if failures occur before a sense of efficacy is firmly established” (Bandura, 1994, pg. 1).

11. Vicarious experiences – “Seeing people similar to oneself succeed by sustained effort raises observers’ beliefs that they too possess the capabilities to master comparable activities required to succeed” (Bandura, 1994, pg. 1).

12. Social persuasion – The process of being persuaded by peers or other trusted individuals that you have the skills or ability to succeed (Bandura, 1994).

13. Physiological response – The physiological reduction of stress reactions and the altering of negative emotional proclivities within an individual’s physical state. This method of increasing self-efficacy is especially influential in athletic or physical activities (Bandura, 1994).

Summary

The ideology related to classical Christian education is becoming increasingly important to the educational landscape of America as CCE continues to grow and expand both in America and globally. This chapter serves to introduce the problem to be studied and the purpose of the research to be performed as it relates to the perceptions of classical Christian school students. Understanding or having a description of these perceptions, should they result in positive findings, would encourage stakeholders to invest more deeply into the outcomes of the pedagogy. To the contrary, should the findings result in negative perceptions from the student, there may be a call to reevaluate the motives of parental and professional practitioners. This study will seek to describe the essence of what it means to be a classical Christian school graduate.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

Overview

The intent of this research is to determine how modern classical Christian students describe their own lived experiences throughout the trivium stages of learning. Given this intent, Chapter Two provides a review of the relevant literature associated with CCE and student perceptions of the pedagogy in general. The chapter is organized into four major sections: the overview, materials covering the theoretical framework guiding the study, a discussion of the current and seminal related literature revealing the need for study, and a summary analysis of the literature that addresses CCE and student perceptions of the pedagogy.

An extensive search for literature written on CCE and its students’ perceptions was performed, including the use of academic libraries and databases such as Academic Search Complete, Education Research Complete, ERIC, EBSCOhost, Proquest Educational Journals, and Teacher Reference Center. This search yielded few philosophical results and even fewer empirical studies (Stanek, 2013). Considering this deficit of literature, Chapter Two presents the relevant philosophical material in order to provide a historical foundation for CCE. Chapter Two also presents the empirical literature relevant to the theoretical framework and student perceptions of lived experiences within educational environments. This material is synthesized to provide an overview of similar and relevant research. Finally, the chapter concludes with a rationale for why this study was performed.

Theoretical Framework

Albert Bandura developed the SLT throughout his writing and work during the 1960s (Lamorte, 2016). Eventually he published the seminal work on the matter entitled Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1971). Bandura posited that individuals obtain new information and mimic behaviors through observation, imitation, and modeling. As Bandura’s (1986) thinking developed on the matter, SLT came to be knows as Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) as it was grounded in the paradigm of reciprocal determinism (LaMorte, 2016). With the shift, Bandura (1986) stated that behavior influences and is influenced by three proposed factors (behavioral, cognitive, and environmental). He later came to acknowledge these factors were the criteria in the development of individual success. This belief in individual success came to be known by Bandura (1986) as self-efficacy.

Self-Efficacy

According to Bandura (1986), self-efficacies are the beliefs individuals hold regarding their ability to produce certain desired results. He determined that the self-efficacy of a person impacted how objectives or challenges were approached. Bandura (1994) ascribed certain traits and norms to individuals who possessed high self-efficacy: challenges were viewed as assignments to be completed, interest developed as participation occurred, they showed a commitment to completing task, and they possessed a high level of perseverance in the face of adversity. Alternatively, Bandura (1994) ascribed counter norms to individuals who possessed low self-efficacy: challenges were avoided, they perceived themselves as incapable of completing tasks, they focused on failures or negative results, and saw adversity as coinciding with a lack of ability. Bandura’s (1993) theoretical framework continued to develop and became even more specific with the application of self-efficacy to educational settings for students. In fact, Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy and its applications to countless arenas has become one of the most investigated subjects within the social sciences (Huebner, Gilman, & Furlong, 2008).

Academic Self-Efficacy

Bandura (1993) found that students’ beliefs in their ability to control individual learning tasks and show mastery on difficult academic tasks affected their academic motivation and thus their achievement. Additionally, Bandura (1994) found that ASE empowered students to persist through adversity and afforded endurance and enhanced performance. Pajaras (1996) defined ASE as a student’s belief that he or she can successfully engage in and complete an assigned task. Bandura (1997) stated, “Educational practices should be gauged not only by the skills and knowledge they impart for present use but also by what they do to children’s beliefs about their capabilities, which affects how they approach the future” (p. 176). Bandura (1997) believed that students with a strong ASE are even prepared to self-educate if left to their own devices.

As applied to this study, the ability of students to perceive academic success should impact their description of their experiences within the phenomenon of CCE. ASE was the specific component of the broader SLT used to frame the research questions of this study and Bandura’s (1986) four predictors were used to classify participant descriptions. Mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasions, and physiological responses served as the framework for how the student descriptions of lived experiences were organized and developed in the narrative that follows (Bandura, 1986).

Related Literature

Classical Christian educational settings are certainly in vogue, but not for the reasons typical of parochial or independent schools (ACCS, 2106). During the early 1990s Christian families across America began to band together to bring about educational reform and protest their opposition to and disappointment in public education (Veith & Kern, 2001). Perrin (2004) asserted, “Constant change and novelty can themselves grow old, becoming the cheap promise of radical newness, which is the most boring and repetitious of all modern ideas” (p.4).

Stakeholders looked intently for an educational program that was the “passing on of wisdom and knowledge; cultural transmission” (Perrin, 2004, p. 4). From this reformation was born the ACCS, its schools, and the Classical Conversations homeschool co-operative movement.

Christian Education

In the 1920s and 1930s non-parochial Christian day schools were a rare phenomenon in America and most evangelical Christians saw little need to challenge public education (Johnson, 1990). However, the Christian school movement has grown significantly in America since that time, due to the outspoken nature of Christian educational reformers and the desire of some families to flee the dangers of secular educational venues. Christian educational reformer’s polemical speech has sparked debate not only between secular and Christian educators but also among Christian educators themselves (Johnson, 1990). The reason for the former is that some modern parents chose Christian schools for various reasons other than the original rationale for their establishment: deliverance from drugs, premarital sex, teen pregnancy, gangs, or violence (Johnson, 1990). In other words, some parents chose Christian schools because they were private, rather than because they were Christian.

However, Christian education is not at all like secular education, be it private or public. Van Til (1990) stated that non-Christians believe the universe created God, whereas Christians believe God created the universe. Because of this distinction, the Christian educator’s duty is to bring the child face to face with God and to understand God’s creation. The secular educator practices a Godless education determined to bring the child face to face with the universe. Understanding this difference dictates that Christian education not be defined as religion that is a condiment that may be added to the neutral territories of life (Van Til, 1990).

For the purpose of this study, I defined Christian education as it is defined by the ACCS. Never viewing religion as a condiment, the ACCS (2016) depends on the biblical passages of Deuteronomy 6 and Ephesians 6 as the foundational principles for Christian education. In the Shema (Deuteronomy 6) the people of God are commanded to love God and keep his commandments. Furthermore, the people of God are commanded to teach these commandments to their progeny. The Shema concludes with,

You shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. You shall bind them as a sign on your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates. (ESV)

Orthodox Christianity interprets this passage as the passing on of truth from one generation to the next, during the completion of the most mundane task of life. This is not simply the transmission of knowledge as occurs among the soulless animals by instinct. Rather, this is the transmission of a way of living among one another in harmony and peace, and an inculcation of a particular body of information. In this sense, education is one dimension of fulfilling the original mandate for humanity to multiply according to the command of Genesis 1:28-29 (Pratt, 2003).

In the apostle’s letter to the Ephesians, Paul admonishes Christian families to live in a particular way. Ephesians 6:1-3 stated,

Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. Honor your father and mother (this is the first commandment with a promise), that it may go well with you and that you may live long in the land. Fathers, do not provoke your children to anger, but bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord. (ESV)

The ACCS (2016) interpreted Paul’s statement as a commission to parents to bear the burden of education. Additionally, the ACCS believes their function as a school site is to be a tool in the hand of the family and an extension of the authority of the family (ACCS, 2016). It is the family’s responsibility to educate their children. And when faced with such a grand task, Christian families commonly look to find the best tool available in achieving their objective. This Latin concept of in loco parentis (in place of the parent), combined with the development of paideia in students while at school is the minimum standard for accredited member schools (ACCS, 2016). Additionally, the ACCS (2016) statement of faith is rooted in the traditional, conservative Christian orthodoxy inherent in the Apostle’s Creed.

Christian education is not only grounded in scripture, but certain pedagogical practices are also informed by scripture. Gunther and Horner (2018) look to the book of Job to produce a clearer understanding of divine pedagogy in the Scripture. Using the teachings of Calvin, in his Institutes, the doctrine of the clarity of scripture, and progressive covenantalism, Gunther and Horner (2018) established what they believed to be a theological foundation for Christian education and biblical pedagogy. Elihu asked in Job 36:22, “Behold, God is exalted in his power; who is a teacher like him” (ESV)? Gleaning from the wisdom of Elihu, Gunther and Horner (2018) asserted that Christian educators should gain greater insight into pedagogical practices by examining God’s revealed intent and practice of instructing his people in Scripture. God’s pedagogical activity in redemptive history should inform the practice and craft of Christian educators (Gunther & Horner, 2018).

Three conclusions were drawn from Gunther and Horner’s (2018) research. First, they found that all areas of study ultimately point to Christ as revealed in Scripture, though some do so more indirectly. Second, in Christian education the study of Scripture should be foundational and should be integrated across content areas in order for students to make connections as they seek to understand the breadth of God’s purposes in creation. Third, God accommodates Himself to His people throughout Redemptive history, and thus sets the precedent for Christian educators to do the same with their students. God’s revealed instruction and model for teaching establishes the proper practice of Christian and biblical instruction.

Trivium-Based Education

The trivium, a core principle of classical education, is comprised of the qualitative arts. It was coined during the middle ages by the Romans and refers to “the three ways” (Perrin, 2004, p. 7). The trivium is the first three stages of the seven liberal arts: grammar, logic and rhetoric (Perrin, 2004). Grammar is the study of the system and structure of language: etymology, prosody, and allusions (Circe Institute, 2018). Logic is the study of reasoning, namely, consistency, soundness, and completeness of the argument (Circe Institute, 2018). Rhetoric is the science of persuasion. Mastery level students understand the use of hyperbole, irony, and alliteration (Circe Institute, 2018). Analogously, Sayers (1948) makes the claim that each of these components come together in the function of the trivium to naturally align with the development of children so that teachers can, when properly informed of these norms, teach in accordance with student’s natural development.

Grammar. In trivium education, grammar (content) is not just a subject, but rather the primitive years of schooling (primary and intermediate elementary) where the building blocks of knowledge are delivered (Wise & Bauer, 1999). Wilson (2003) asserted, “Grammar is not simply linguistic, but should be understood as the constituent parts of each subject” (p. 132). The importance of this stage is the mastery of content so that dialogue and winsome communication about the topic can later occur (Littlejohn & Evans, 2006). During the grammar stage of learning, the rules of phonics and spelling, rules of grammar (as a subject), poems, the vocabulary of foreign languages, the timelines and stories of history and literature, descriptions of plants and animals and the human body, the facts of mathematics, etc.…these make up the “grammar,” or the first stage of learning (Wise & Bauer, 1999).

Logic/Dialectic. The second phase of trivium education, the logic (thinking) stage occurs in middle school and is a time when the student begins to pay attention to cause and effect, to the relationships between different fields of knowledge, to the way facts fit together into a logical framework, or the way the parts or building blocks are ordered (Wise & Bauer, 1999). The memorized piles of data obtained in the grammar stage must be sorted and categorized. But not only are the parts sorted into categories, but the ideas are also evaluated as to good and evil, truth and goodness (Wilson, 2003). It is here where the student’s capacity for abstract thought begins to mature (Wise & Bauer, 1999). Wilson (2003) asserted that discernment for the teacher at this level is critical as students are learning, in brief, who the good guys are and who the bad guys are, who is right and who is wrong. “To learn that a duck is not a horse occurs in the grammar stage. To understand that a horse is a more suitable animal for battle, belongs in the dialectic stage” (Wilson, 2003, p. 135).

Rhetoric. The third and final level of trivium education, the rhetoric (expression) stage, occurs during the high school years, after the student learns to write and speak with force and originality. “The study of rhetoric, according to Quintilian, concerns the art of a good man speaking well” (Wilson, 2003, p. 133). Building on the first two stages of learning, the master student of rhetoric applies the rules of logic learned in middle school to the rudiments or foundational information learned in the grammar stage and communicates with wisdom and eloquence. He expresses his conclusions in clear, forceful, winsome language. Wilson (2003) said, “Polish without substance is sophistry. Substance without polish is…well, actually we don’t know because nobody pays attention” (p. 133). It is in the rhetoric stage where students begin to specialize in whatever branch of knowledge attracts them (Wise & Bauer, 1999).

Historical Foundations of the Trivium

Some debate exists among educational philosophers on the derivation of liberal arts education and the ancient trivium and quadrivium. There is no record of any Greek educator specifically outlining a curriculum that consisted of the seven arts. It was the Romans who began to systematize the arts into a specified universal curriculum (Marrou, 1982). While many hold that it is rooted in the philosophical writings of Plato and his protégé, Aristotle, (Marrou, 1982; Vitanza, 1997) others ascribe that it belongs to the rhetor, Isocrates of Athens (436-338 BCE). Marsh (2010) contends, “The legacy of the educational program of Isocrates has a remarkable consistency: for more than two millennia, it has engendered both controversy and commendation” (p.289). Plato and Aristotle believed it to be misguided and lowbrow while Cicero and Quintilian both believed it to be the most successful educational program (Marsh, 2010). For the purpose of this study, the ongoing debate over ascribing origin to a particular philosopher is not germane to the research or the affected literature. Therefore, only a brief discussion of the individuals who impacted the origins of the trivium or its development through the ages will follow.

Plato. Jaeger (1933) maintained that the Greeks invented the notion of education, by which he meant the original idea of training youth to pursue the ideal conception of the human being. This concept of education, according to Jaeger (1933), is liberal arts education from the platonic perspective. Kimball (2010) asserted that Jaeger’s choice of Plato as the originator of the liberal arts was perfectly consistent, inasmuch as Plato was one of the thoroughly idealistic theorists of education. Even more specifically, Marrou (1998) believed that all theories of education in Ancient Greece took their origins from Homer, the poet. In The Republic, Plato wrote the following,

When you meet encomiasts of Homer who tell us that this poet has been the educator of Hellas, and that for the conduct and refinement of human life he is worthy of our study and devotion, and that we should order our entire lives by the guidance of this poet we must love and salute them. (Plato, trans. 1945)

Marrou (1998) identified this following as “a heroic morality of honour” (p.33). “Just as the Middle Ages bequeathed The Imitation of Christ at its end, so the Greek Middle Ages conveyed The Imitation of a Hero to classical Greece through Homer” (Marrou, 1998, p. 33). This morality, in Plato’s philosophy, became known as paideia, and thus became the unshakeable nucleus of resistance that empowered the soul of the educated to fight against the elemental forces of the world (Bazulak, 2017).

Isocrates. Jaeger (1944), contrary to his original assertion, later declared that a direct line can be traced from our own modern classical pedagogic methods back to Isocrates who had far greater influence on educational methods of humanism than any other Greek or Roman teacher. The educational goals of Isocrates can also be isolated to a basic understanding of the concept of paideia. Marsh (2010) defines paideia as the philosophy and program of a pedagogy that generates the ideal citizen. The concept of citizenship emphasizes the communal nature of education for the Greeks. This definition is similar to Wilson’s (1999), the founder of the modern movement of CCE and the ACCS, who said that paideia was the all-encompassing enculturation of future citizens.

Isocrates believed that his task was making students wise, enabling them to direct the community toward progress and newer possibilities. The foci of his educational goals for each student was moral improvement, service to the state, composition skills, eloquence, and kairos (Marsh, 2010). Kairos is one of two Greek words for the concept of time and refers to one’s ability to seize the moment or capitalize on the opportunity when presented. Each of these concepts are integral to the modern understanding of the trivium and are common goals for CCE (ACCS, 2016). They are also visible in early American democracy and western civilization’s educational ideology (Oldenburg & Enz, 2017; Sayers, 1948; & Shokri, 2015).

Isocrates developed students through a course of study or curriculum that later came to be known as the trivium (Muir, 2015). It was the Isocratic tradition that established liberal education and the seven liberal arts, including the trivium and the quadrivium (Muir, 2005). Finley (1975) reported the Isocratic version of liberal education, with a specific inclusion of the trivium and quadrivium divisions, “passed from the ancient Greeks to the Byzantine world, from the Romans to the Latin West, where it continued to dominate medieval education in Europe” (p. 199).

Cassiodorus. Wilson (2003) ascribed responsibility for organizing elements of paideia into what are now called the seven liberal arts to Cassiodorus. Cassiodorus equated the seven liberal arts with the seven pillars in the house of wisdom from Proverbs 9 (Wilson, 2003). Cassiodorus was born in southern Italy around 480. According to Boyd (1921), Cassiodorus planned the establishment of Christian schools in Rome that would integrate sacred literature instruction with training in liberal arts. He emphasized a sevenfold grouping of knowledge and provided sanctity to the idea by interpreting Proverbs 9 as the seven liberal arts. Graves (1910) asserted, “So it is to Cassiodorus primarily that we owe the organization of these educational elements into seven areas” (p.27).

While Cassiodorus is commonly known for his writing of ancient texts used in the Roman educational system, he also established one of the first institutions known as a university in the monastic tradition (Drane, 1910). At the age of 83, Cassiodorus wrote his treatise De Orthographia, which was the predecessor of two works that served as curriculum guides for his students entitled On the Teaching of the Sacred Letters and On the Seven Liberal Arts. The later expounded on each of the seven arts and served as the seminal work to inform later elementary texts used during the middle ages (Drane, 1910).

Augustine. The Dark Age is the name given to the time period most closely associated with the fall of the Roman Empire (Marrou, 1982). As the Roman social and political structures began to collapse during the fourth and fifth centuries, so too did the Classical Schools of antiquity. It was at this time that Aurelius Augustine, the Bishop of Hippo, publicly and skillfully began to wed the concepts inherent in the liberal arts with the teachings of Christianity. It was as though the Dark Ages served as a womb that nurtured and developed Christian education. Paradoxically, the pedagogy was grounded in the pagan trivium and quadrivium of the seven liberal arts from the previous century (Marrou, 1982). As the Dark Ages descended, it was evident that the governance and institutions of the Classical Schools of antiquity were damaged beyond repair. What took their place, were the monastic, Episcopal, and Presbyterian schools (Marrou, 1982).

The monasteries were established for the training of the monks who served as teachers and the Episcopal and Presbyterian schools trained the clergymen. The two functions of priest and teacher were thus intimately associated with one another and so pedagogy became an important topic of study once again.

Augustine was leery of pagan contamination. In his work On Christian Doctrine he stated, “The disciplines of the pagans are unclean, because there is no wisdom in those who do not have faith.” Yet it was under Augustine’s leadership that the concepts inherent in the trivium were carefully adapted to train Christians (Wilson, 2003). Twelfth century Benedictine theologian Rupert of Deutz said of the liberal arts, “They have bowed to their mistress, wisdom, and have been redeployed and bidden to sit down”. Wilson (2003) commented, “The liberal arts have abandoned their previous promiscuity, have been brought into the household of wisdom, and are now chaste” (p. 122).

By elaborating on the educational system of the seven liberal arts, Augustine established a Christian methodology for education, which remains significant in the modern sense and worthy of attention in terms of educational research (Stancienė & Žilionis, 2006). Modern classical Christian educators are indebted to Augustine, who modeled the careful integration of the pagan liberal arts to Christian theology and educational practices (Wilson, 2003).

Classical and Christian Education

The study of classical philosophy within a Christian educational setting may seem paradoxical or even contradictory as the Greek classics are believed by some to bring harmful influence over the spiritual mind (Mot, 2017). Glanzer, Ream, and Talbert (2003) asserted that the attempt to teach virtue from a distorted, in this case classical, historical tradition is destructive for stakeholders. Variance of belief on the subject is demonstrated by the vast array of denominations within orthodox Christianity, but also the many definitions and purposes presented by those denominations for what Christian education should be. In spite of these beliefs, ACCS members do not agree that education in the classics should be demonized as described above. On the contrary, the classics are to be scrutinized and studied in light of scripture and the Christian worldview (ACCS, 2016). More so, the pagan beliefs of the ancient cultures, the folly of the pagan gods, and the egregious effects on the Christian church should be recognized for what they were; the escalation of sin in the absence the gospel (ACCS, 2016).

The terms classical and Christian merge most appropriately with a proper understanding of the concept of paideia. By Christianizing and re-deploying the liberal arts, Augustine brought back into focus the idea of educating and enculturating citizens. This was inherent to both classical Christian educators and the original philosophers who envisioned the trivium and the quadrivium (Marsh, 2010). The concept was also the focus of Augustine’s work in The City of God. The allegory contrast two cities, the City of Man and the City of God. The Augustinian concept of humanity’s fallen nature, man’s tendencies toward individualism, and the soul’s yearning for redemption is persistently described within the City of Man. However, those who dwell in the City of God basked in perfect enculturation (paideia) and experienced salvation (Gruenwald, 2016). Paideia represented the shaping of the ideal man, who would be able to take his place in the ideal culture. Classical and Christian education is the process of bringing that culture about (Wilson, 1999).

Cheryl Lowe, classical Christian educator and founder of Memoria Press wrote a tenvolume article entitled Why Christians Should Read the Pagan Classics. Lowe (2012) gave ten reasons why it is important for Christians to consider the work of non-Christians from the classical era as not only relevant, but also essential for educating covenant children. Lowe (2012) asserted the following:

Pagan classics provide the foundation for all human knowledge and that, without them, we have no hope of making sense of history or our modern world. The pagan classics are the indispensable foundation of a classical education and, what is more, they provide the key to unlocking the errors of modernism. For the Greeks did more than get some things right; they asked all of the important questions and either gave us the right answers or laid the foundation upon which answers could be found. It is not too much to say that the providence of God prepared two sources of light—one human and one divine—and both are needed to defend and preserve our civilization and our faith. (p. 1)

Lowe’s (2012) rationale, while not formally endorsed by all ACCS accredited member schools, certainly provides a sample opinion that is common among its members. The ten reasons why Christians should read the classics were as follows:

1. Architecture: Scale, mass, proportion, and symmetry—the principles of classical architecture—were worked out by the Greeks in great detail and built upon in succeeding generations.

2. Virtue: The Greeks were the world’s first systematic, abstract thinkers and are most famous for their study of things immaterial, the world of metaphysics, the human soul, ethics, and virtue.

3. Science: The abstract investigation of the natural world began with first principles of Greek philosophy.

4. Education: Classical education focuses on the study of the classical languages of Latin and Greek, and on the study of the ancient civilizations of Greece and Rome.

5. Natural Law: Ancient philosophers first asserted, aside from the particular laws that each people has set up for itself, there is a common law that is according to nature and is universal and binding on all men.

6. Government: The founding fathers of all free peoples were inspired and influenced first and foremost by the democratic republic of ancient Greece.

7. Religion: Many of the early patriarchal Church fathers believed it was the philosophical prodding’s of Cicero, and the Greeks who always asked the right questions, that eventually led them to Christ.

8. Philosophy: The Greeks were the first to ask, how do we know what we know?

9. The Human Condition: While the Bible gives us the clearest picture of the human condition, the high ideals of Socrates and the Greeks show the Gospel was not just good news to the Jews.

10. Literature: Without the study of ancient texts, our study of literature will remain superficial, insufficient, and incomplete.

Modern classical Christian educators were certainly not the only to wrestle with the idea of blending Christian perspectives with the format and content of the classics. Tertullian asked most famously, “What does Jerusalem have to do with Athens?” Many of the Magisterial Reformers debated the inclusion and implementation of the classic pedagogy in their Christian education (Wilson, 2003). Calvin, in opposition to his reformation colleagues, Luther and Melanchthon, supported the use of the liberal arts in training young, Christian minds (Wilson, 2003). Calvin asserted in Boyd (1921),

Although we accord the first place to the Word of God, we do not reject good training. The Word of God is the foundation of all learning, but the liberal arts are aids to the full knowledge of the Word and not to be despised. (p.198)

Dawson (1989) describes the reformation period as not only a time of theological reform but educational reform as well. As the Reformation swept across Europe, educational institutions designed curricular programs to include training in religion, systematic theology, Latin grammar, and the study of the classics (Dawson, 1989). These schools of the reformation deployed a classical Christian education (Wilson, 2003).

Contemporary Theorists of Classical Education

Not all approaches to classical education are created equal. In fact, three major models are currently in operation among independent schools in America. The schools associated with the Paideia Proposal movement inspired by Mortimer Adler provide a democratic classicism (Littlejohn & Evans, 2006). The vein of schools associated with David Hicks and his Norms and Nobility movement provide a moral classicism (Littlejohn & Evans, 2006). Finally, the ACCS member schools associated with Douglas Wilson and his work entitled Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning provide a Christian classicism (Veith & Kern, 2001). Each of these models have their respective historical foundations that informed their philosophy. Adler was Aristotelian with his commonsense approach. Hicks was inspired by Plato as he focused on idealism and saw education as a means to virtue. Lastly, Wilson was inspired by Isocrates and Augustine, as ACCS schools continue to teach with an awareness of human sin and the need for the grace of God (Veith & Kern, 2001).

Adler. In the modern sense, Mortimer Adler was one of the earliest proponents for reinstituting a classical education (Ravitch, 1983). Early in Adler’s teaching career he developed the notion of the great books of western civilization as a course of study. It was launched in 1920 at Columbia University during a two-year seminar course (Chaddock, 2015). Twenty years later, Adler published his best seller, How to Read a Book, that forged the idea into a movement. Originally, Adler sought to promote fine literature for the sake of pluralism, inclusiveness, civic virtues, and as a pathway to democratic culture (Chaddock, 2015). The context for the movement was the rise of progressivism and ideology within pedagogy during the late 1930s among professionals in schools of education and influential groups such as the National Education Association (NEA) (Ravitch, 1983). Adler served as a critic for professional educators, forcing them to defend their foundational principles for pedagogy development. In 1982, with the assistance of The Paideia Group, Inc., his criticism developed into a philosophy and curriculum in the published work entitled The Paideia Proposal (Ravitch, 1983).

Adler’s Paideia philosophy was instrumental in the establishment of public and private schools across America. Research from schools in Chicago, Cincinnati, and Chattanooga suggest that Paideia reforms have positively affected classroom climate, academic interest, and democratic self-governance (Paideia, 2018). Adler’s (1982) greatest critique against professional educators was there laser focus on vocational training instead of liberal arts education. Adler’s work heralded five guiding principles: (a) learning begins in the child’s mind and “it cannot therefore be created by a teacher,” (b) all children are educable, (c) learning is a lifelong process, (d) the teacher must use multiple teaching methods to best enhance the child’s learning of subjects, and (e) the goal of education should not be to prepare a child for a later vocation (Robins, 2012). As an educational practitioner, Adler believed similar to the Greeks, that vocational training was for slaves and liberal arts education was given to all free citizens (Robins, 2012). Because all individuals were free in Adler’s social context, naturally he believed all should be given a liberal arts education, hence the democratic classicism.

Hicks. David Hicks, former president of St. Andrew’s Episcopal School in Jackson, Mississippi, believed the chief aim of education is the teaching of virtue, defined by dogmas of the past (Berard, 1983). Pitts (2011) asserted that Hicks defined classical education as an attempt to develop virtue in each student by recourse to an investigative paradigm that recognizes the importance of mythos, the imaginative domain, in conjoint activity with the logos, the realm of reason. For Hicks (1981),

Classical education is not, preeminently, of a specific time or place. It stands instead for a spirit of inquiry and a form of instruction concerned with the development of style through language and of conscience through myth. The key word being inquiry. (p. 18)

Education was never about the learning of facts or the assimilation of those facts into categories; rather education is “the habituation of the mind and body to will and act in accordance with what one knows” (Hicks, 1981, p. 20).

As a critic of public schools, Hicks (1981) believed graduates, while able to master a variety of technical skills, remained incapable of coping with technological or social change as persons or citizens. His 1981 work, Norms and Nobility: A Treatise on Education demonstrated his distaste for empirical educational research, educational theory, and teacher professional development. Alternatively, he suggested practical curricular alternatives rooted in rigor that included the inclusion of Shakespeare’s Richard II and More’s Utopia as required reading for seventh-graders (Berard, 1983). His philosophy carried the belief that every graduate would be introduced to the most profound thought and writings of western civilization. Mimicking the Greeks, Hicks believed that he could provide the perfect mix of intellectual, cultural, and spiritual formation, known as paideia or moral classicism (Berard, 1983).

Wilson. Douglas Wilson is a reformed, evangelical theologian and pastor of Christ Church in Moscow, Idaho. He is also currently on the faculty at New Saint Andrews College and is a prolific author and speaker who advocates for a distinctly Christian model of classical education (ACCS, 2016). With the support of several families and fellow administrators, Wilson (2003) opened the Logos School and helped to establish the ACCS as an accrediting organization for CCE. In so doing, Wilson (1991) missioned to recover the lost tools of learning originally

identified by Dorothy Sayers (1948) in a speech delivered to Oxford University.

As for how Christian classicism compares to the democratic and moral classicism, Wilson (2003) stated, “The ACCS approach to education is specifically and distinctively Christian, and hence it is more dogmatic and settled than what either Adler or Hicks would propose” (p. 84). Wilson (2003) believed that both Adler and Hicks failed to capture the essence of the trivium as a whole. While Hicks focused mainly on the dialectic (logic) and Adler was most interested on the capstone nature of rhetoric, Wilson (2003) and ACCS schools are driven “to move students from grammar to dialectic, and then from dialectic to rhetoric” (p.84) To remain in any of the three during the tenure of a student or to focus solely on one level would be considered a failure by Wilson (2003).

Yet, it isn’t only modern Christians who have realized the benefits of classical Christian education. Vance (2016) studied the impact that classical education had on the Brothertown Nation of Indians, the composite tribe created by Christian members of seven Algonquian towns located around the Long Island Sound. Vance (2016) traced their migration from New England in 1783 to the Brothertown area and described how the town was organized around a combination of Algonquian principles and Connecticut town laws. While Brothertown has long fascinated scholars, Vance (2016) emphasized how historians have chosen not to give import to an instance of cultural adaptation (classical education) that powerfully shaped the movement. Vance (2016) “reinterpreted the Brothertown movement in the context of its founders’ classical education, which scholars have generally mentioned in passing or even dismissed as irrelevant” (p. 140).

In his study, Vance (2016) surveys how Eleazar Wheelocks, a Congregationalist minister, educated 66 Native Americans, while simultaneously operating his Moor’s school for AngloAmerican boys and missionaries. Wheelock’s approach to education was similar to the British missionary mindset, in that the Native Americans had to be assimilated into British culture before being converted to Christianity. However, what was unique was Wheelock’s commitment to classical education as the means to assimilate. Vance (2016) described this classical education as Latin education, rooted in western culture, using a set of pedagogical principles and norms that affected the Native Americans in “complex and unforeseen ways” (p. 140).

Borrowing from Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, Vance (2016) investigated the interactions between classical education (known during Wheelock’s time for its inherent elitist spirit) and Native American cultural norms. Vance (2016) defined Bordieu’s habitus as “internalized expectations” (p. 141) that informed actions, habits, or predisposed responses congruent with learned norms. Wheelock’s students were trained in how to behave and educated by teachers whose worldviews were steeped in British missionary practices. They endured the heavy emphasis on western civilization, participated in the foreign language exercises commonly performed in the ancient texts, adhered to the rigid daily schedule, and even endured the physical beatings and behavioral modifications common to the Latin schools. The probing question most relevant to this particular research was what affect did classical education have on the founding of Brothertown, and through its founding, what was the social heritage left of classical education? Vance asserted, “Their education incentivized them to adopt and fuse Algonquian and Anglo norms in specific ways, and the movement that resulted” was a subset of Native Americans, a portion of which who became the founders of the Brothertown community (p.141).

Vance (2016) concluded that two major principles were evident from his research. First, in spite of the elitist mentality associated with classical education during Wheelock’s time and other times in history, the Brothertown community demonstrated that Latin grammar instruction and classical educational principles were not only to be associated with wealthy, Caucasian male scholars; but disenfranchised minority groups were also intellectually capable of interacting within the confines of those principles. Vance (2016) discovered females, African Americans, and Algonquin Indians that had successfully integrated into the classical conversations at different times and in different regions of the world.

Second, Wheelock was determined to use classical education to assimilate the Algonquin to Anglo-American norms. However, something all-together different occurred. The tool proved to be divorced from the agenda and the Algonquin people used Latin and classical educational principles for distinctly Algonquin purposes (Vance, 2016). “Wheelock saw Indian/Christian and Indian/Latinist as irresolvable binaries and did not realize that his students could use their classical education to further Algonquin-centric agendas” (Vance, 2016, p.164). The Vance (2016) study shows the effectiveness of the pedagogy in this particular context as well as the reforming mindset of those who have attempted to implement CCE principles.

Classical education is old. As Perrin (2004) stated, “It was new with the Greeks and Romans over 2000 years ago as they were credited with constructing the rudiments of the classical approach to education” (p. 6). Modernity has brought about the adoption of a revitalized classical education with a new framework; the integration of a protestant, Christian worldview (Veith & Kern, 2001). With the modern influence of protestant, Christian thought, CCE is grounded in the study of western philosophy, Latin grammar, formal logic, and winsome instruction in rhetoric; also known as trivium-based education (Circe Institute, 2018).

Contemporary CCE Research